![]()

Write us!

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net

UPRISING IN ARGENTINA

Argentine Workers Fight for Survival, Drive Presidents from Office

by Bob Mattingly

“We don’t have any money, we are hungry, and we have to eat!” shouted a woman taking what food she could get her hands on, as cops fired tear gas and rubber bullets on a desperate crowd breaking into markets, carting away slabs of meat and plastic bags full of food and clothing. Shop owners killed at least three people that day, the press reported.

In the week before Christmas, anxious, jobless workers in cities across Argentina took to the streets, attempting to cope with the ravages of four years of “recession” and slashed social budgets. Reportedly, nearly half of the nation’s population is at or below the official poverty line, with unemployment officially at over 18 percent. “If only that were true,” a union activist said in disbelief, “that would be good news.”

Industrial production fell nearly 12 percent in November over a year earlier, and hundreds of factories have closed. Argentina’s president announced eight highly unpopular austerity plans during his two years in power, including a 13 percent cut in the wages of state workers and moves to slash pensions and raise taxes.

Hoping to blunt the rising hunger and poverty, the government began disbursing more than 400,000 pounds of food aid—mostly meat, rice, powdered milk and vegetables. At the same time, the government declared a state of siege to contain the worst civil unrest in a decade, according to reports.

|

| A stockbroker is euphoric as the International Monetary Fund offered Argentina $8 billion in aid August 22, 2001. —Daniel Luna/AP |

General strike

A week earlier, the “whole of Argentina was largely paralyzed [for a day] as a result of a general strike,” which was organized by the country’s three main labor unions. The day before, there were “street protests, which included marches, rallies, roadblocks, blackouts and ‘caceralazos’—in which residents standing in windows or on balconies bang pots and pans at a given hour.

“In Cordoba, a car-making center northwest of Buenos Aires, workers [were] protesting government plans to reduce wages and apply other austerity measures,” reported the BBC on December 20. The protesting workers “occupied the town hall, then set light to the ground floor of the building. Police dispersed the demonstrators using tear gas and rubber bullets.”

Mainstream reports at first called the hungry Argentines who took to the streets “looters,” “rioters,” and “gangs.” But the day after the state of siege was declared, the press began to call the people in the streets “demonstrators” and “protesters.” By then the “protesters” were counterattacking “with flying rocks and paving stones,” massing in front of the ornate governmental palace, and demanding that the regime resign in response to the government’s prohibition of public gatherings and its threat to make arrests without court orders.

Despite mass arrests and over 25 deaths; facing truncheons, tear gas, water cannons, and cavalry charges by mobilized police forces, the popular insurgency spread throughout the country. After four tough years of belt-tightening and waiting for a better day, the politics of food, clothing, and shelter became the order of the day for ordinary people. And many of those people demanded that the nation’s president resign. Late Thursday (Dec. 20), the president, Fernando De la Rua did resign and rescinded his state-of-emergency decree.

As De la Rua fled the palace in a helicopter, he no doubt hoped that the protesters would leave the streets. But some protestors had other ideas. “We want them all out, not just De la Rua, but all of the political leaders. This is a wakeup call: We’re fed up with this country’s political class,” one said. Another told the press, “The past few days were ugly, but many more are ahead.”

The International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) sent a message of solidarity, but some protesters might have thought the union officials’ hopes were naïve. “We at the ICFTU fully affirm our support for the strike action carried out by our affiliated member, CGT. We hope that the government, in whatever form it may take, will finally begin to pay attention to the needs of the workers and the social costs of mismanagement.”

Imperialist press predicts “rough times”

More realistically, New York Times editors on Dec. 21 opined that, “Argentina will most likely have to devalue its currency and pass through even rougher economic times before it can begin a recovery.” That’s because, say many analysts, devaluing the nation’s currency means instant bankruptcy for countless Argentines and many of the biggest businesses. So the editors also knowingly implied that if the masses spurn the prospect of “rougher economic times,” then military repression might follow. “It is a painful process, and one that can be managed only if political stability is restored and maintained, and if the army stays out of politics.”

A Wall Street analyst told the Times he expected “a period of intense political turmoil and escalating civil unrest, a deeper economic collapse, imminent default and an indefinite debt moratorium with the likely total loss of control of the currency.”

An interim president, Rodriguez Saa, announced a temporary halt to crippling interest payments on Argentina’s $132 billion public debt partly owed to international investment institutions and partly owed to Argentine investors who made their investments from outside the country, hedging their bets. Saa said the freed-up money instead was to “be channeled into social assistance for the poor, and into the creation of jobs.” A dockworker shrugged and said, “Hopefully, things will get better, … but I’m not holding my breath.” And indeed, he should not. For as The New York Times explains, “The deepening economic crisis … has much to do with a slowing world economy and declining agricultural export prices, which no Argentine government can control.”

But the Times isn’t exactly right. A workers’ government not indebted to Argentina’s propertied class would have economic options that are foreclosed to the wealthy and their political accomplices. For one thing, it would have the confidence of the majority. It could nationalize the nation’s idle plants and workplaces and resume production. It could ensure that the nation’s agricultural and industrial production is fairly allotted to all (presently the wealthiest 10 percent skim off 48% of the nation’s income). It could prevent the nation’s earnings from being siphoned off into the coffers of foreign investment banks by strictly controlling its international trade. And it could fend off attempts to return to the undemocratic control of the economy by providing for the arming of the people as a whole.

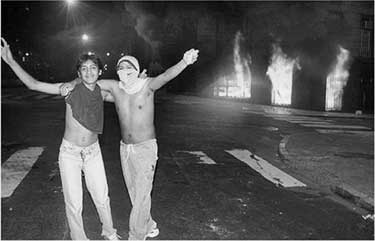

|

| Buenos Aires demonstrators celebrate as the Economic Ministry building burns—AP |

Socialist left growing

There are signs that for several years, the political momentum of great numbers of people has been moving away from the traditional political parties, all of which are complicit in the nation’s present severe economic crisis. For example, in the recent October legislative elections, 20 percent of the population reportedly did not vote (even though voting is mandatory), and another 20 percent voided their ballots. The socialist left racked up an impressive 1.3 million votes, nearly 12.5 percent of the total; the biggest vote the Argentine left has ever won. And of course, the extra-parliamentary ousting of two presidents from office in just a few days indicates that the political momentum of the people is increasingly hostile to the parties of the bankers, industrialists and the big landowners.

Encouraging, too, is the self-activity of growing numbers of people who are organizing outside of the bureaucratic leaderships of the established social movements and trade unions. Trade unionists, unemployed, small farmers, petty merchants and student youth together are forming regional assemblies, which are hotbeds of resistance to the many forms of the stagnation and depression that rack the economy.

These assemblies, aren’t councils of worker’s deputies, that is, soviets of the 1917 Russian Revolution type; nor are the assemblies communes on the order of the innovative Paris Commune of 1871. The assemblies may only have a transitional viability. That remains to be seen. But to the extent that they allow people to directly make decisions and carry out those decisions free of bureaucratic encumbrances and impediments, to that extent they serve as an invaluable weapon against the pitiless private property system and the political state that serves it.

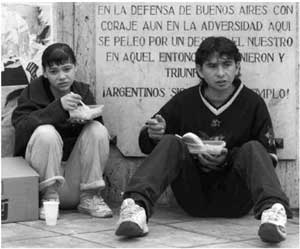

|

| A young, hungry couple have a free lunch at the Plaza Miserere on August 26, 2001, the Day of Solidarity. One out of every three in Buenos Aires makes less than the minimum needed for food, clothes, and services. —Enrique Macarian/Reuters. |

The biggest challenge to the Argentine workers, the impoverished middle classes, the hungry and the poor will come from Uncle Sam, the same power that has armed the South American military forces precisely for the purpose of preventing the liberation of the people’s in its “backyard.” If the masses hesitate or pull back from today’s social and economic abyss, the door will be opened for military repression.

The Argentine ruling elite may not lose its control this time around. But its options are narrowing and the rulers say as much. Argentine politicians are pressing for $1.3 billion in aid from the reluctant International Monetary Fund—“which much of the world, with considerable justification, views as a branch of the U.S. Treasury Department,” says New York Times economics columnist, Paul Krugman (Jan. 1). During the first days of the insurgency, the finance minister told the press that without IMF money, “we’re dead meat.”

Write us!

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net